War reporter Alex Quade takes you behind the stories of Special Operations. She shares more personal stories and challenges behind her Edward R. Murrow Award-winning work covering Special Operations Forces in combat. Extreme storytelling and silent risk-taking are at the heart of what Alex does. [Read more…]

Search Results for: behind the stories of spec ops

An Exclusive Look At Special Forces In Alex Quade’s ‘Danger Close’

By Ford Springer

Entertainment Reporter, The Daily Caller

Alex Quade began covering war zones in 1998 and was almost perpetually embedded with US troops in Afghanistan or Iraq from 9/11 on. Her new Hollywood documentary, “Danger Close,” focuses on her time on the ground with Special Operations Forces starting in 2006 with brief glances at the many dangerous missions she covered. [Read more…]

‘The house that Rob built’: Special Forces Combat Outpost Pirelli, part 2

GOLD STAR FAMILY

U.S. Army Special Operations Command holds a ceremony for families of fallen operators at Fort Bragg, N.C. every Memorial Day. Gold Star families from the past year meet each other and learn they are not alone, as the command gives them tours and lunches. They learn more about what their sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers did.

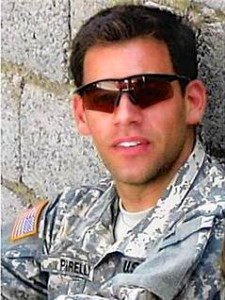

Rob’s sister Stacey & father Bob Pirelli (Photo courtesy Pirelli family)

The Pirellis braced themselves by reiterating that Rob was a hero.

“His captain summed it up by saying, ‘Rob never turned back; he never ran. He served forward.’ And they [his A-Team] didn’t stop: they finished the mission for Rob,” the senior Pirelli told me.

Bob Pirelli’s tattoo in honor of his son. (Photo courtesy of Pirelli family)

It was pouring at the solemn ceremony. An honor guard stood at attention while rivulets streamed down the faces of Green Berets, Rangers, and “Night Stalkers” (members of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment). A bell rang after every name killed in action. Team liaisons escorted families to the remembrance wall to read the name of their loved one freshly engraved in the dark marble, and to leave carnations.

As team liaisons Chief Warrant Officer Jim and Engineer Aaron escorted Bob and Stacey Pirelli to the wall, Bob froze. He turned back to me with tears in his eyes.

“I can’t do it,” he said and hugged me. Chief Jim looked at me annoyed.

“Yes,” I whispered in his ear firmly, “You can.”

“Do it for Rob,” I said. “Rob would want you to do it for his team who is back over there [in Iraq] right now.” The father immediately pulled himself together and walked forward with his daughter to the wall.

After the ceremony, Bob told me that he believed his son was watching over his Team re-deployed to Iraq.

“I know that every day they must think of Rob, because I hear it in their telephone calls and emails,” Bob said.

“We trusted Rob with everything; trusted him with our lives,” Chief Jim said. “He was the guy who you knew would be there to support you no matter what was going on. We’re always looking out for each other, that’s the way pretty much all SF is. It’s a team,” he added.

Rob Pirelli’s grave site. (Photo courtesy of Pirelli family)

One morning, he found it vandalized.

Someone had backed into it with a truck, knocking over the headstone.

Bob blasted photos and angry notes over the internet: Who would do something like this? Desecrate a hero’s resting place?

An investigation found a family member involved. As often happens after deaths: tragedy, grief and stress can bring families closer together — or deepen already established rifts.

“Rob told me in a dream to ‘Just let it go,” Bob said. No charges were filed.

He moved to Albuquerque, N.M. to start over. Other family members made the closest thing they could to replicate the “Combat Outpost Pirelli” cement T-wall in Iraq for Bob’s front yard: a four foot tall, 300-pound slab of rock with “Combat Outpost Pirelli” engraved into it.

Father Bob Pirelli’s memorial stone-slab in New Mexico, in honor of his son. (Photo courtesy of Pirelli family)

BACK TO THE HOUSE THAT ROB BUILT

This time in Iraq, ODA-072, Rob Pirelli’s team, was deployed to a different location in the south: An Nasiriyah, near Ur, Iraq’s most famous archeological site with remains of a ziggurat or temple.

The A-Team’s safe house was tucked away inside a massive Forward Operating Base at Tallil Airbase — a far cry from their Combat Outpost on the fringe.

“They are folding my laundry this time,” Medic Tim said when I arrived. “I knew that this kind of deployment existed. It’s completely different than the last deployment. Honestly, there’s times where I’m like, ‘Man, I wish we were back up at COP Pirelli.’ They have some nice luxuries here, but the whole, you know, uptight garrison thing. Reality at this base is making sure they have their PT belts on,” he joked.

Communications Sergeant Kevin, who temporarily became “Team Daddy” under fire, explained that the threat the team faced at this location was different, too.

“Last year, it was al-Qaeda that we were up against, plus there was the contested area between the Arabs and the Kurds. Here it’s primarily JAM [Jaysh al-Mahdi, a militia defending Sadrist political institutions and Muqtada al-Sadr’s interests,] you know — Iranian influence.”

Besides Pirelli, some of the other original team members were gone, too. Team Sergeant Don continued to recover from his injuries, as did Weapons Sergeant Scott. Engineer Aaron had been hurt on a training mission in Colorado.

“I now have two cages and 8-screws fusing [my back] together. At the same time, I started having grand mal seizures. The doctors attributed it to the four IEDs which did some brain damage in my frontal lobe,” Aaron said.

So I asked the familiar faces on the team about Rob Pirelli, one year on.

“It sticks with you, and you think about it all the time. People say, ‘don’t second guess yourself,’ but you second guess yourself no matter what — think about what you could have done better, what you should have done better,” Captain Jason said. “But that’s, I guess, what happens in any incidence like this.”

“Human nature,” I offered.

“I stay up sometimes at night just thinking about it. And people who say ‘Don’t second guess yourself,’ are generally people who have no idea what they’re talking about, and who have never been through an experience like that. That’s exactly what you do when a situation like that happens. There are lots of times when I just get pissed off about what happened and, ‘If I could have done things differently.’ But you just have to learn to accept it. That’s life. That’s what God decided to have happen on Aug. 15 of 2007,” Captain Jason said.

Intelligence Sergeant Brady, who’d shared a room with Rob during the last deployment, said Pirelli would have enjoyed poker night at this location.

“This deployment is a little weird without him. It’d be nice to have him here. A lot of things, he really helped out. I think his dad does understand that we as a team respected Rob a lot. He’s still in all of our minds at all times, and in everything we do. So he’s still here with us,” Brady shared.

I asked the A-Team if it was tough to talk about their buddy killed in action.

“It’s a good reminder what the ultimate price is, and what you’re willing do to. I think it’s a good everyday reminder,” Intelligence Sergeant Brady replied.

For Medic Tim, it was a realization of how far he’d come since his days with Pirelli — and Dan, a guy from another team — in their Special Forces Qualifications Course to become Green Berets.

“Back in the Q-course, if you’d said: ‘You’re gonna get to a team, and on your first deployment, two guys are gonna get shot and one is gonna die…’ You know, back then, I would’ve thought I would be way more a mess now. But it hasn’t affected me like I would have expected. I mean, I definitely miss Rob every day,” Medic Tim explained.

I emailed Medal of Honor recipient Col. Jack Jacobs for his thoughts for this Team.

“In my experience the shock doesn’t appear immediately. It is later – often much later – that the real ravages of loss take their toll, and we will have to be vigilant long after we will have left the arena of combat,” Jacobs shared.

“Everybody has some problems with that [survivor’s guilt,] from time to time. You always look back, especially as a leader, knowing that things might have been different, and lots better, if you had done something different. But you know you can’t re-live yesterday. Tomorrow is what counts,” Jacobs added.

War reporter Alex Quade covers Medic Tim’s “motivation exercise” with his Iraqi Foreign Internal Defense (FID) force. (Photo courtesy of Alex Quade)

“We made some significant changes up there. I imagine that the teams after us took it even further and further. It would just be interesting to see what it’s evolved into,” Medic Tim admitted, showing me his “COP Pirelli” tattoo on his arm.

I’d already promised Rob’s father that I’d try to get back to Combat Outpost Pirelli. I added the A-Team’s request, too.

But Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force Arabian Peninsula public affairs officers said, “No.”

They said my embed was officially with 10th Group, not with 1st Special Forces Group who was currently in Diyala. It didn’t matter that I’d covered 1st Group last year in Baghdad.

Since they would not let me embed with the 1st Special Forces Group team currently at Combat Outpost Pirelli, I did the next best thing: I embedded with conventional forces that were now living on the same property as the old Team house.

A PLACE CALLED “COBRA”

Alex Quade covering 10SFG & Iraqi FID force in Iraq. (Photo courtesy of Alex Quade)

“We just got a coffee pot two days ago, after three months of being here, so we’re getting re-adapted to caffeine!” First Lt. Andrew Parton from Nashville, Tennessee, told me as we walked through the “moon dust” around the compound. This was his first deployment.

“We’re cowboys and Indians. We’re out here on the frontier. The rest of the units are back in Baqubah. We’re still working on the amenities. We have no women here. In fact, you’re the first woman we’ve seen in like three months,” Parton laughed. “We have few accommodations or facilities here,” he warned me.

His Stryker Cavalry Scout Platoon from Alaska (part of the 5-1 Cavalry Squadron known as the “Arctic Wolves”) were technically a reconnaissance, surveillance and target acquisition squadron.

“We’ve been called everything from ‘War Dogs’ to ‘Circus Freaks’, so that’s pretty much our range out here,” Parton said.

Unlike the Special Forces unit co-located at that location, the conventional forces conducted most of their missions during the daylight hours. The Recon Scouts were covering the exact turf I’d covered one year before with Green Beret Staff Sgt. Rob Pirelli’s ODA-072 — specifically, the villages of Tibij, Tenara, and Jalula.

“When we were told we were going out to Diyala, there was a unit here before us that had some pretty intense stories. So we came in here ready to see some heavy action. We know the enemy is sitting back, watching us. They’re learning our procedures and how we conduct ourselves, and different tactics we use. We’re waiting for ‘em to come at us. But we’re ready for it. It’s inevitable. We all know it is,” Parton brought me up to speed.

One mission involved clearing the village of Tibij — again. The Recon Scouts were trying to get their Iraqi Army partners to search houses. One sergeant I followed on the patrol asked me to not use his name.

“We go with them when they search a room, make sure they’re doing it right, and honestly, it hasn’t really changed. Even when mentoring, they still search the same way. They still have their friends there, they have people they talk to, and if they think that the person in the house is ‘good’ then they don’t bother searching,” the sergeant said.

I asked if this was frustrating, as we walked slowly through the village.

“Yeah. It just makes the timeline in my head, like, we’re never gonna leave ‘cause they’re not ready,” he said.

They patrolled past a pile of rubble that had been a building.

“Was that a house?” I asked the sergeant.

“It was a hospital. The insurgents blew it up before we got here,” he replied.

“Why do you think they blew it up?” I asked.

“Because they’re insurgents. Could be a couple different reasons. Could be it was a bunch of thugs trying to raise some chaos. Could be an insurgent group trying to pressure this town into cooperating with them,” he answered.

Another mission involved clearing palm groves around the village of Tenara — again.

“The Iraqis all say this town is safe. But, a week ago there was an IED. So this town’s safe? Yeah, the insurgents are here,” First Lt. Parton said before we dismounted the Stryker to patrol on foot through a palm grove, which also had orange trees, to look for weapons caches.

“We know they [the insurgents] have lots of relatives. Family’s still family here in Iraq. And these ladies that live in this house could still be angry at coalition forces; still trying to support the insurgency. So they might be, you know, hiding caches, or even insurgents themselves,” Parton explained.

Before his Recon Scouts arrived at “Cobra” (the former COP Pirelli,) there had been a female suicide bomber, Parton said.

“Women are just as bad as the men,” he added.

“These bad guys out here, these are the higher level guys that are leading the insurgency. These aren’t just the foot soldiers. These are the guys that are planning operations, financing operations and gathering intelligence on us. These guys, they stay low. They try to get other people to do their work for them. They know what they’re doing. All the dumb ones are dead,” Parton elaborated while I walked behind him through dense vegetation along a trail in the palm grove.

One of the sergeants was trying to coax his Iraqi Army counterpart to use his machete to cut a cleaner path.

“It looks like they’re going the wrong way,” I said quietly to the sergeant who asked not to be identified.

“That’s ‘tactical movements,’ ma’am,” the sergeant said with a smirk.

“Hey sir, got some holes dug over here,” the sergeant said to the lieutenant.

Then, shots fired.

“Someone’s running out of the palm groves,” came across the radio.

“Two guys were running out!”

“But there were shots fired. Did they shoot someone?” Parton asked his interpreter to ask his Iraqi Army counterpart.

“Hey, tell him we heard shots fired, ‘boom-boom-boom,’ okay? I’m wondering where those shots came from,” Parton said.

“I think police,” the interpreter replied.

“Iraqi Police? Okay,” Parton said as we moved deeper into the grove.

“Where is his… does he know where his guys are?” Parton asked the interpreter to ask the Iraqi Army leader over the radio.

BOOM!

The deafening explosion was close. The shock wave startled everyone and whipped branches around us. Iraqi voices shouted.

“Was that a Stryker?” The lieutenant yells. “Start moving back to the vehicles!” Parton tried to discern if we were under direct fire attack or if an IED had gone off in the palm grove.

“Negative. No one had visuals. We’re moving back to the vehicles now. We’re going to get out,” the sergeant says over the radio. “L-T [lieutenant,] explosion right there. There’s the smoke right there.”

“Where’s the IA [Iraqi Army] captain at? Do you got injury – do you got casualties? Where’s the IA captain?” Parton shouted at the interpreter.

“Smoke. It’s just to the side of our position,” the sergeant says over the radio to the Stryker team outside the palm grove. “Hey, gunners: be advised we’re moving out of the palm grove.”

“Stay with us… up here! And spread out!” Parton shouts to his Recon Scouts and Iraqi Army soldiers. “Hey! Spread out you guys! Keep eyes for f**king trip wires! Sh**! Sorry about that,” Parton says to me about his use of swear words as we run through the palm grove.

“Back a little bit here. Keep moving! Keep moving! Keep moving! Keep moving! Hey, keep eyes to the north also. Hey Neil [another Sergeant,] can we get out there? I want to make sure that the IA doesn’t have casualties,” Parton shouts.

“Okay, Sir. We’re going to med-evac,” the sergeant answers as we keep moving.

“Where we going now?” The lieutenant asks as we wind our way through the foliage. “You see the smoke?”

“It was in the palm groves,” comes word over the radio.

“Exactly! In the palm groves. F**k! Sh**! Get down!” Parton shouts as we hear gunshots and drop to our knees in the bushes.

“Uh, they’re not close,” the sergeant says. “If you hear them snap, they’re getting close.”

We find our way back to the edge of the palm grove and the Strykers on the dirt road.

“Have this vehicle move with us, all right, for cover,” the lieutenant says as we walk towards two flaming cars, billowing with dark smoke just ahead of his Strykers.

“Good sh**. That’s good sh** making them rush over there right now. Good f**king sh**,” one of the sergeants mutters sarcastically under his breath as we walk towards the vehicles which had exploded.

“Hey, put these guys up front,” the lieutenant directed the Iraqi Army troops to take the lead.

The dark outlines of people are inside the flaming cars. Civilians crowd around trying to douse the fire. The Iraqis try to get the smoldering people out of the two vehicles and into the back of a Toyota pick-up turned make-shift ambulance.

Someone eventually produces a fire extinguisher. The dead driver of one car, charred black, is finally dragged out of the vehicle and left contorted on the dirt road. Onlookers crowd around. A bed sheet is eventually produced to cover the corpse while the wreckage continues to smoke heavily.

A large improvised explosive device took out the two civilian vehicles. Five Iraqi civilians were severely injured. One was killed. A nearby brick wall had a massive hole in it from the force of the blast. Car parts were blown across the dirt street on top of a house; its windows broken.

“We’d just rolled past there about twenty minutes before the actual explosion. Which leads us to believe that either our electronic jammers are working, or else it was remotely detonated. It’s ironic. Just yesterday we were on a humanitarian mission a click [kilometer] from here. We dropped off candy, soccer balls and school supplies,” Parton said to me while his men waited for an EOD (explosive ordnance disposal) team to arrive.

“This wasn’t a homemade, kind of a hasty IED. It was a well-planned bomb,” he added.

I asked a senior sergeant about it.

“The locals knew that you guys and the Iraqi Army are out here — doing this clearing operation yesterday — and that you were coming back today, right?” I ask.

“Today. Roger. They knew we were here. They knew, ‘cause we came out that way, and then we came around through this road, so they knew we were in this area. Unfortunate accident. Pretty sure it was made for one of us: the coalition forces, Iraqi Army guys or the IPs [Iraqi Police.] The civilians just happened to be unlucky,” the sergeant said. “IED, then small arms fire.”

“It was scary at first ‘cause it was kind of close,” another Cavalry Scout quietly came up to me while we watched the vehicles smoke off. He was a sergeant from Indiana.

“Definitely got everybody woke up. I felt the shock. Thought it was a mortar round that had come into the palm grove, ‘cause it hurt my ears, shook my arm a little bit, from the shock wave,” he said.

“Who was shooting?” I asked him.

“The IA [Iraqi Army] told us that it was the IP’s [Iraqi Police] that were shooting. We don’t know what they were shooting at. They tend to do that at times. They tend to just open up in the immediate area. They got all pissy,” he said.

Back at Combat Outpost Cobra (nee’ Pirelli), we learned that the Iraqi Army soldiers found a secondary device not far from where we’d been.

Parton’s Recon Scouts handed me a blunt K-Bar knife before he escorted me over to the Special Forces Team House (the house that Rob Pirelli built) where I would hitch a helicopter ride back to Baghdad. They said I’d “earned my spurs,” but didn’t have any to give, so the K-Bar would suffice.

The lieutenant was excited to walk me “over to the Special Forces side” of the base, because his conventional forces weren’t allowed there.

At the original COP Pirelli, after being cleared by security guards (“force protection”) and video cameras, we knocked on the door. A tall, rough-looking, 1st Special Forces Group Soldier with a dark beard opened it with a hard stare.

“We know who you are,” he said directly at me.

He escorted us to the “TV Room” inside COP Pirelli, to wait for the 160th SOAR (Special Operations Aviation Regiment) helicopter to arrive. Either this current team, or the one who’d taken over from ODA-072, had up-graded the TV Room: they’d built stadium flooring so every chair could see the big-screen TV. And, there was now a huge collection of DVDs.

I noted other changes inside the former ODA-072 Team House: three additional portraits of Special Operators killed in action in this area now hung on the wall across from the famous freezer, along with a photo of Rob Pirelli. This Special Forces area of operation was obviously still dangerous. Rob’s “This is Sparta!” sign was on another wall.

I asked the tall, dark-haired 1st Special Forces Group soldier if they called this Team House “COP Pirelli.” He didn’t know what I was talking about. I mentioned the painting on the cement T-wall outside. He said they thought that was just “another painting on a T-wall.” They didn’t know Pirelli; he was just another Special Forces soldier who’d sacrificed. So I told him about the “Senior Charlie” and his team, ODA-072, and that “this was the house that Rob built.”

The team house began to rumble. The bird was inbound. I grabbed my rucksack, eye and ear protection and we rushed passed Rob’s “COP Pirelli” T-wall towards the Blackhawk helicopter. The area where ODA-072 had parked its up-armored vehicles was now a landing zone. The 1st Special Forces Group soldier handed me off to the 160th SOAR crew.

At least, I thought on the night flight back to Baghdad, I fulfilled my obligation to Bob Pirelli and Rob’s A-Team to be able to give them an update on Combat Outpost Pirelli.

—

Over the years, I kept checking in on Combat Outpost Pirelli, despite its other name designations. For me, the location became an interesting barometer of change.

In 2009, the second anniversary of Pirelli’s death, an A-Team from 5th Special Forces Group was manning the former “COP Pirelli.” They too, called the location “Cobra.”

In 2010, three years after Pirelli’s death, members of a conventional forces unit I’d covered in 2008 were at Cobra, which was turning into a full Forward Operating Base.

Staff Sgt. Daniel Snider had been part of the appropriately named “Cynic Platoon.” His 2-14 CAV (Stryker Cavalry platoon from Hawaii) were now covering the same stomping grounds as Pirelli’s ODA-072 had, three years prior.

The last time I’d covered Snider’s men on patrol, they’d had, as they called it, “the suckiest job in all Iraq.” Their mission included repeatedly searching two “trash villages,” or massive garbage landfill dumps, near Camp Taji, Iraq for “hot spots” and hidden weapons caches. I’d followed his Cynic Platoon on one of these pungent patrols over Christmas time in 2008.

Snider’s men, then, were roughing it at a new joint firebase with few amenities. It had an Iraqi name which the U.S. troops couldn’t pronounce, but sounded something like “Fatty-cat,” so that’s what they called it when the brass wasn’t in earshot. At the time, it reminded me of Combat Outpost Pirelli.

“MREs [Meals Ready to Eat]. No water. No showers. Only get to turn laundry in every tenth day. I mean, you know, what’s not to have fun about? Living the American soldier life, you gotta love it,” Sgt. First Class Carey Buchanan said to me in one of his platoon’s Strykers during a mission.

Breakfast for many in this platoon consisted of: Marlboro cigarettes, coffee, Tic-Tacs and diet pills for energy, chased by “a little purple pill for heartburn.”

“Put your nose clips on boys, we’re going into Trash Village today,” Staff Sergeant Snider said to everyone over the radio. I asked what he meant.

“Oh man. I’m gonna have to clean out my Stryker, I’ll have flies in it today. I’m gonna have the smell on me. But we have to go through the two trash villages, and yeah, it stinks. You can’t stand the smell and there’s gonna be thousands of flies around you. It’s just part of the deal, I guess,” Snider explained.

“We’ve gone on cache hunts before where our mission was to go out to a certain area, and we’re walking through ‘poo-water.’ Up to our knees in ‘you-know-what.’ And there’s been times where we drove down some route and one of our Strykers fell into a hole and so now we’re in there trying to dig our Stryker out of ‘poo-water’,” Snider elaborated.

Everything they were doing was a joint operation with the Iraqis they were advising. I asked if this was a sign of progress.

“It’s like ‘Lord of the Flies’ all growed-up. But, they’re getting better,” Sgt. First Class Buchanan said. “If you had saw them a year ago, I mean, they’d go on a patrol with us in flip-flops,” he added.

Now, in 2010, Staff Sgt. Snider’s men were responsible for advising Iraqi Army and Kurdish Peshmerga Soldiers at five trilateral checkpoints around Forward Operating Base Cobra’s territory in Diyala Province, where Rob Pirelli’s A-Team (ODA-072) had long ago built rapport with Kurdish fighters and cobbled together that initial Iraqi Foreign Internal Defense Force.

“The IA and Pesh [Peshmerga] run the checkpoint. We are there to make sure they don’t fight, basically. We have gotten them to work together and run a checkpoint together, which is impressive, since they’ve fought each other for so many years,” Snider said.

I asked him about “COP Pirelli.”

“I know SF [Special Forces] have special missions that are completely different than what we get to do,” he laughed, “And the mission set is completely different now with the SOFA [Status Of Forces Agreement pending in 2011] changes and giving their country back to them,” Snider added.

As for the danger factor around Forward Operating Base Cobra, Snider’s men hit two IEDs and still faced the occasional small arms fire.

“The insurgents targeted a pipeline in our area and the leadership of that project. They target the Iraqi Police that roll around. They target the city councils. Their focus is more against the locals than U.S. forces, but they have targeted us a few times,” Snider explained.

Snider was just happy that here at Forward Operating Base Cobra there was laundry and no “trash villages,” like at the last location I saw him.

—

Over these years, Rob Pirelli’s former 10th Special Forces Group teammates redeployed to Iraq again, as well as to other locations around the world.

Meanwhile, Bob Pirelli, wrote email notes to his son in an online condolence book.

“No one knows how many times I have broken down and cried,” the elder Pirelli wrote once.

Another time, it was: “Son, they say there is a reason… they say time will heal… but neither time nor reason will change the way I feel.”

As anniversaries of Rob’s death came and went, more emails from Bob Pirelli: “Miss you Son, just wanted you to know your thought about on this day and always. Love you – Dad.”

FOURTH ANNIVERSARY: “DON’T FORGET US”

In August 2011, on the fourth anniversary of Green Beret Engineer Rob Pirelli’s death, the conventional troops co-located with the Special Forces element, now called the house that Rob built: “COS Cobra,” or Contingency Operating Site Cobra. It had also been called a Contingency Operating Base and then a Contingency Operating Location. Whatever its name (not Pirelli), it was still a dangerous area.

“Threats leaving the [gates of the] COS include: small arms fire, IEDs, hasty and deliberate attacks — attacks from insurgents associated with violent extremist organizations,” a 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division public affairs officer told me. “Mortars and rockets fired from the surrounding neighborhoods continue to be a main danger,” she added.

The troops from Fort Hood, Texas, drove MRAPs around that area of Diyala Province now, rather than the “old” Stryker vehicles. The “Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected” vehicles were the latest class of armored fighting vehicles designed to help them survive improvised explosive devices.

“There’s still people here that want us gone, want to kill us,” Sgt. Robert Simmons, a 35-year-old medic from Fayetteville, N.C., said at COS Cobra.

Simmons explained that everything was in draw-down mode due to the SOFA (Status Of Forces Agreement.) The remaining checkpoints — which Staff Sgt. Daniel Snider’s men had controlled the year prior — had transitioned to a bilateral stance, meaning the Iraqi Army and Peshmerga soldiers had taken control. Simmons’ men from Fort Hood were in an over-watch position.

“Still feels like war. Might not be where rounds are flying. But we still have a sense of danger. We still have a threat that forces us to keep our eyes on,” Simmons said.

The public affairs officer clarified: “Elements of al-Qaeda and Jaysh Riijal Al Tariq Al Nazshadbanda – JRTN – are still in the area.”

“I want folks to know that we’re still over here fighting and dying and not to forget us,” Sgt. Simmons added, “We still need your support.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the sprawling Contingency Operating Site Cobra, a 5th Special Forces Group Operational Detachment Team from Fort Campbell, KY, was now living in Pirelli’s old Team house.

That A-Team’s intelligence sergeant explained, while he did not personally know the first Green Beret killed in action there, Rob’s name still meant something to the Special Operations Forces community four years on.

“Paintings on T-wall barriers, named after him, help us to remember who he was. As our history grows he will always be remembered as one of our Special Forces heroes who gave up his life so that others could remain free,” the Green Beret said at the Team house.

The “Combat Outpost Pirelli” cement T-wall protective barrier still guarded the northern entrance to the operations center.

“The team there does regard it as a memorial and are taking care of it,” Dan, a Green Beret from another team said. (Dan, who’d gone through the Special Forces Q-Course with Rob Pirelli and Medic Tim, was also redeployed back in Iraq.)

“I’d seen the [insignia] crest on Tim and Bob [Mr.Pirelli’s leg,] but hadn’t seen the crest on the wall. Now I’ve seen it. It’s pretty moving. It’s symbolic. Got a little bit of Rob in it. It’s not a good thing [because it means a SF soldier was killed in action]… but most guys kind of seek it out,” Dan added.

“As it stands now, the Pirelli T-wall will stay in Iraq. However, it will be blown in place immediately before our team departs – we’re not leaving it for the Iraqis,” the 5th Special Forces Group’s Intelligence Sergeant at the team house added vehemently.

Despite their pending departure due to the Status of Forces Agreement at the end of 2011, the Special Forces team was still taking the threats around their area of responsibility seriously. It was, after all, the same stomping grounds which Pirelli’s Team, ODA-072, covered four years ago.

“Bad guys include Shi’a extreme terrorists and Sunni insurgents. Specific threats include IEDs, VBIEDs, suicide bombers, magnetic IEDs,” the intelligence sergeant said.

“The Iraqi Army is taking the lead and face the majority of the threats and dangers, the U.S. forces are taking an advising and assisting role,” the public affairs officer interjected. “The Team continues to follow command guidance in maintaining a relationship with Iraqi Army Forces as well as Kurdish forces in the AO [area of operations,]” he added.

“Despite what looks like ‘no news’ from here [in the media] we stay very, very busy and with our partner guys,” Dan, from another A-Team, told me.

According to the public affairs officer, only 4,500 U.S. Special Operations Forces were left in Iraq at that point.

“There’s a very real threat. Not like Ramadi or Fallujah in ’04: we’re not sleeping in our body armor anymore. It’s a subdued threat, but still very big. Not only to us, but to our Iraqi soldiers and to everyday Iraqis,” Dan added. “There’s certainly a sense of things winding down, but it’s not relaxed by any means. Even the bad guys know it. There’s a pause.”

At the time, I asked Lt. Gen. John F. Mulholland, then head of U.S. Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, N.C., about his Special Forces troops’ imminent departure from Iraq and about those killed in action, like Engineer Rob Pirelli.

“Iraq has a democratically-elected government and professional security forces that are assuming their role in protecting their citizens. Our Army Special Operators – through their work alongside these forces – have made a lasting contribution to freedom there,” Mulholland responded.

A PIECE OF THE WALL

Meanwhile, back at Fort Carson, Colorado, home of the 10th Special Forces Group, some members of Pirelli’s old team marked the 4th anniversary of his death in a different way.

“A bunch of Special Forces Green Berets will dress up in silly costumes [ranging from Spartacus to Elvis] and ride mountain bikes down from the top of Pike’s Peak,” Medic Tim said. “We’ll then pub crawl from Manitou Springs to Colorado Springs to revel in rowdy behavior in honor of Rob Pirelli, killed in action on Aug. 15, 2007,” he added.

Medic Tim explained that the tradition was to raise money for a memorial fund set up in Rob’s name.

“Wish I could be back [in the U.S.] for the bike ride,” Dan, the Green Beret from another team said in Iraq. “Been talking with Tim about trying to do something here [in Iraq] for Rob on the same day. But the location we’re at is not sustainable for bicycling. I’ll go to the gym and do a rowing type of event,” Dan planned.

“We’re not sure how long we’re going to row for, I’ll check with Tim. We will make it extremely difficult. When were finished we won’t be able to remember our middle names and probably be lying in a pool of our own sweat and vomit,” Dan added.

Around the fourth anniversary of Pirelli’s death, Dan, from the other A-Team, rowed in solidarity in Iraq, while his Special Forces brothers mountain biked down Pike’s Peak, Colorado. But he was forced to cut it short, because a mission came up.

“Most important thing to me is to keep my son’s name alive, because as the years go on, people are forgetting,” Bob Pirelli said from New Mexico.

Not long thereafter, the COP Pirelli T-wall was demolished.

Rob’s memorial photo, along with the photos of four other U.S. Special Operations Forces warriors — who over the years lived in that compound and were killed in action in that same area — also came down.

Rob’s “This Is Sparta!” hand-painted sign was removed.

On Sept. 8, 2011, American forces handed Contingency Operating Base Cobra to the Iraqi Security Forces. “Dark Horse” soldiers of the 4th Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment from Fort Hood left behind buildings, cement barriers, and non-military equipment.

A little known part of that handover: the secret Special Forces “Team House” tucked away within the bowels of the conventional forces base that had built up around it like urban sprawl.

“We had Rob’s wall broken into pieces so the Iraqis can’t have it,” Dan, the Green Beret from another team confirmed. The painted pieces of the Combat Outpost Pirelli T-wall were wrapped up and placed in a military shipping container for eventual distribution to the Pirelli family, Medic Tim, and the 10th Special Forces Group.

Future residents of Diyala, Iraq’s most dangerous province, will never know that this was the house that Rob built.

“I knew it [the Combat Outpost Pirelli T-wall and the Team House] wasn’t going to be there forever. It was an outpost, like what we had in Vietnam, where we had temporary locations,” Bob Pirelli, who’d served in the Marine Corps, said. “So, I’m not saddened – because that piece [of the Pirelli T-wall] is what’s important to me, and it’s just shifting ground [from Diyala, Iraq, to his home in the U.S.],” Pirelli added.

The Gold Star father, fighting stomach cancer in New Mexico, was taking comfort in jotting personal notes to his fallen son, in an online condolence book, whenever he felt physically up to it.

“You are my last thought before I fall asleep,” Pirelli wrote to his son before the last U.S. troops left Iraq in December 2011. Special Forces Green Berets were amongst the “last guys” to depart.

“Rob, as your 5th anniversary approaches, remember your always missed by so many hearts you have touched,” Pirelli wrote. “Watch over us and know that there is never a day that passes without the thoughts and memories you instilled on us. Love you son.”

FIFTH ANNIVERSARY: “ONE DAY AT A TIME”

Memorial at Northeastern University in honor of Rob. Bob & Stacey Pirelli in front row. (Photo courtesy of Weapons Sergeant Scott)

Northeastern University, where Rob studied criminal justice, held a memorial. The town renamed a street and a hockey arena, where he played as a Panther goalie, after him. And every November, a comedy club night raises money in Pirelli’s honor for a high school scholarship fund. (For more information: contact the Staff Sgt. Robert R. Pirelli Memorial Fund, P.O. Box 365, Franklin, Mass., 02038.)

“Just because it has been five years, doesn’t make it any easier, any better, or any different. It is what it is. And I struggle with it every day,” Rob Pirelli’s mother Nancy told her daughter Stacey on the 5th anniversary of Rob’s death.

“Even though I understood that he was putting his life on the line, I never expected things to go the way they did. Which is probably the main reason why the reality of it is still so shocking to me,” Stacey Pirelli said.

“I have my not so great days. But more often than not, I overdo my talking about my brother, because for me, it brings Rob back to me, and nothing beats that,” Stacey added.

Bob Pirelli said, it’s harder now, as he fought stage four stomach cancer. His goal was to “make it” to Franklin for the 5th Annual “SSG. Robert Ryan Pirelli Comedy Show.”

“They raised $20,000 last year for the high school scholarships. It was another sell-out. The next one, Stacey wants to make very special. So the fifth one, this November will be the best,” Bob said.

When Mr. Pirelli moved to Arizona for cancer treatment, he brought the Combat Outpost Pirelli 300-pound, “memorial slab of rock” his family members made, from New Mexico too.

“All he can do is keep fighting for himself right now,” his daughter Stacey, Rob’s sister, said. “Our most commonly used statement is, ‘One day at a time.’ We have been living that way since Aug. 15, 2007, but we are really trying to live that way now, more than ever,” Stacey added.

For the Green Berets at Fort Carson, Rob Pirelli’s fifth anniversary was marked quietly. There was no raucous Pikes Peak mountain bike ride as in years past. Instead, they faced the massive wild fires in the Colorado Springs area, while their deployed brothers faced other battles in Afghanistan.

“Guys were calling from overseas asking us to check on their homes and families,” one 10th Special Forces Group sergeant major told me.

“We all miss Rob. And, we all wonder what we could have done differently to change what happened. But, of course, none of us can do that,” Weapons Sergeant Scott said.

“I don’t think about that time without thinking about Rob. I will never forget Rob,” JTAC Mike said.

“The loss of a warrior teammate is felt for a lifetime. The feelings of loss, pain, grief and yes… even guilt are real! One must find a way to deal with all these emotions,” Medal of Honor recipient Colonel Roger Donlon explained to me on the 5th anniversary of Rob Pirelli’s death.

Meanwhile, the Pirelli family and members of 10th Special Forces Group at Fort Carson, held hope the pieces of the Combat Outpost Pirelli T-wall would someday show up.

“They told me Rob’s T-wall was in a military shipping container somewhere after the troops pulled out last year,” Bob Pirelli said. He clinged to the idea that pieces of it would show up in the mail, despite Army bureaucracy.

“The wall pieces will be put into small shadow boxes and distributed with a photo and description. I have it pictured in my head. I think it’ll be great to have another piece of this huge puzzle, that I continue to put together within my life,” Pirelli emailed me.

SEPTEMBER 11th, 2012

Three weeks after the 5th anniversary of Rob Pirelli’s death, his father Bob Pirelli lost his battle to stomach cancer. It was September 11th.

“I find comfort in imagining the joy my brother’s and father’s spirits both felt when they first united again [in Heaven],” Stacey Pirelli said. “Given the choice, my Dad wouldn’t have chosen any other day.”

Stacey said her focus now was to make the upcoming November comedy show tribute to her brother Rob a success, since her father’s goal had been to survive long enough to “make it” to the event so people would not forget his son killed in action.

“My Dad wanted me to do everything in my power to make that happen, so that’s what I will do,” she said.

One of the last things Bob Pirelli did before dying was post a note on Facebook about the comedy show to honor his son.

“Join us as we continue our goal to keep SSG Robert Ryan Pirelli’s name alive through his high school scholarship program,” Bob wrote. “Join the Pirelli Family and share in their journey to remember a ‘True American Hero’.”

Until his death, Bob Pirelli told me he worried that Rob’s sacrifice would be forgotten, especially after his son’s Combat Outpost was turned over to the Iraqis the year before.

Pirelli also worried because official records do not show that outpost in Diyala, Iraq named after his son.

“We submitted the paperwork to higher, about the name change,” Captain Jason said. “But you know Army bureaucracy: it got lost. We still refer to the outpost as Pirelli, even if it’s officially something else.” (When it was handed over to the Iraqis it was called: Contingency Operating Location Cobra.)

VETERANS DAY 2012

Around Veterans Day, the Pirelli family and some of Rob’s former Teammates — Engineer Aaron, Weapons Sergeant Chris, Captain Jason, and Dan, the Green Beret from the other team — celebrated Rob’s life at a comedy show in Milford, Massachusetts to raise money for his high school scholarship fund.

“It was bittersweet,” Rob’s sister Stacey said. “I kept imagining Rob and my Dad would surprise us all by walking into the hall together.”

The next day, Rob’s Special Forces teammates helped his former Panther hockey teammates retire his #18 jersey at the memorial arena named after him.

Operational Detachment (ODA) 072 (Photo courtesy of Alex Quade)

MEMORIAL DAY 2013

Today, Iraq remains deeply dysfunctional. Deadly violence spiraled last week, with more than 240-people killed in car bombings.

“The government is paralyzed and only focused on its own political consolidation,” Kenneth Pollack, of the Brookings Institution said.

Diyala Province remains a microcosm of the entire country. Sectarian tensions between Sunni, Kurd, and Shi’a are well known.

Ramzy Mardini, at the Iraq Institute for Strategic Studies, who tracks Iraq’s security and post-U.S. crisis, says Diyala is ripe for exploiting ethnic tensions and widening the rifts between the different communal and political factions.

“The province is certainly an area where al-Qaeda plans on regaining some of the territorial ground they lost during the counterinsurgency effort,” Mardini said.

Diyala became the second province requesting to hold a referendum on becoming its own federal region, which would allow it to secede into its own semi-autonomous region. This has pitted the Sunnis and Kurds on one side, against the local Shi’as and the central government on the other. Clashes after the federalism bid led to Diyala’s governor fleeing and the province being placed under martial law. There is deep distrust of the government.

“Given its ethnic diversity, all sides have a stake in Diyala,” Mardini added, “the province is a front seat to the political crisis that has riddled Baghdad.”

The area specifically around the former COP Pirelli remains problematic today, according to Michael Knights, at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Knights specializes in military and security affairs of Iraq and the Gulf Arab states, and talks to his government and security contacts in Iraq every day.

“That area is still hot, and complicated. There are still AQI [al-Qaeda in Iraq] operations, but fewer than in 2010-2011 when it was one of the last AQI combat zones. Now the action has shifted to [another part of Diyala province] Muqdadiyah, Baqubah and the ‘Breadbasket’ generally. That’s where AQI is trying to hold orchards once again,” Knights said.

“If Maliki [the democratically elected President of Iraq] does not do something dramatic to reverse these trends, especially given the impact of the Syrian civil war next door, Iraq too could be headed in one of several very bad directions,” Pollack stated.

—-

Meanwhile, back in Massachusetts…

“No tears; just overwhelmed.”

That’s how Stacey Pirelli described her feelings to me, upon finally receiving the piece of the Combat Outpost Pirelli T-wall, six years after her brother Rob was killed.

“That wall really does bring out the good that Rob’s team did, in keeping his memory alive,” she said.

Dan, the Green Beret from another A-Team, tracked down the shipping container after all these years, in time for this Memorial Day.

“The fact that pieces of blown-up rock are from the wall with the insignia that read ‘Combat Outpost Pirelli,’ which was done in memory of my brother’s sacrifice – and that so many of the team guys got tattoos of it, and even my Dad got a tattoo of it – goes to show that Rob impacted the lives of the people around him more than words can explain,” Stacey added.

Staff Sgt. Robert R. Pirelli (Photo courtesy of 10th Special Forces Group)

“It was something of my brother’s that my Dad always talked about,” she said. “To have it is like getting back the missing piece of the puzzle.”

Hard, cement pieces they can hold in their hands — Memorial Day proof of what Rob Pirelli died for.

‘The house that Rob built’: Special Forces Combat Outpost Pirelli, part 1

Editor’s note: Reporter Alex Quade embedded long-term with Operational Detachment Alpha Teams of the 10th Special Forces Group in Diyala province, Iraq in 2007 and 2008. One of those “A- Teams” was ODA-072. Quade covered their training at Fort Carson, Colo. and followed up with them and their families through the years. Per Special Operations Command embed guidelines: No last names of operators were used; military public affairs officers in Iraq, as well as at Fort Carson reviewed every frame of Quade’s video to ensure no techniques, tactics & procedures are revealed. Also, 10th Special Forces Group Operational Detachment number designations changed after 2007. Most team members retired or moved on. They shared their personal photos. Alex Quade returned to Diyala Province repeatedly to cover U.S. troop movements and progress. six-years later, she was allowed to share more information and locations, since U.S. forces and bases are no longer there, after the U.S. military departure. [Read more…]

Reporting from the front lines

Ask University of Washington alumna Alex Quade to describe a memorable moment from her journalism career, and she will quickly rattle off half a dozen. There was the time a Green Beret gunner needed her to help feed more ammunition into his .50-caliber machine gun during a firefight. Or the time she filmed a special combat engineer dismantling a car bomb two feet away. Or the many times she comforted wounded soldiers. The list goes on and on.

Quade (BA, Communication, Speech Communication, Political Science, 1992) is a freelance war reporter who covers U.S. Special Operations Forces on combat missions. She is the only reporter, male or female, who has embedded long-term with these elite secretive units. Quade spends months at a time in the field, using a hand-held video camera and notepad to capture stories about combat, including the personal stories of Special Forces on the front lines.

“My goal is simple: to make the inaccessible feel relevant to the American people,” she says. “I tell the human stories behind the hardware, combat stories from the heart. I want to bring the audience along for the ride, to share the human experience, not strategy nor politics. I want to make people pay attention and shake them out of indifference.”

Before donning combat gear in far-flung places like Iraq and Afghanistan, Quade worked more traditional journalism jobs. She started as a White House Press Office intern, then worked as a producer and reporter for Fox News and CNN. But combat reporting was always her goal. She embedded with an elite unit in 1998 and never looked back.

“I was mostly concerned with not messing up, getting the story, doing what I’m supposed to do,” she recalls of her first time working in a combat setting. “Just like the soldiers I cover, I’d done everything I could to prepare. At that point, it was just ‘game on’ and laser focus on the job ahead.”

That laser focus has helped Quade gain the trust of Special Ops leadership who rarely welcome journalists into their world. “They operate in secret, and it’s high stakes,” says Quade. “What they do has life-and-death repercussions, so they’re not going to let just anyone in. I must prove myself every time: by my candor, courage, integrity, and most importantly, by getting the story right and not being a burden to the teams I’m with.”

Quade has accomplished that brilliantly according to those who have worked with her. Senior Weapons Sergeant James A. Baker, retired Green Beret of the 10th Special Forces Group, recalls that Quade blended in and became part of the A-team when she embedded with his Operational Detachment. “She’s like us,” he says, offering the ultimate compliment. “If there’s another step to take, she’s going to take it and go as far as she can. Not everybody can do that. It’s just who she is. If it can be done, she can do it.”

I tell…combat stories from the heart. …I want to make people pay attention and shake them out of indifference.

“The truth of these soldiers’ lives cannot truly be shared from a TV studio in New York City, or from the occasional anchorperson dropping in,” Quade says. “Freelancing allows me the opportunity to spend more time going out on more missions with the Special Operators, learning firsthand about them and witnessing what they do, so I can responsibly do justice to their stories and answer the questions of their families and the American public.”

Quade’s stories have run the gamut from profiles of Green Berets, to coverage of a fighter jet shot down in Iraq, to the first broadcast interview of the SEAL Team 6 member who shot Osama bin Laden. Her reports air on major TV news outlets and have been published in The New York Times, CNN.com, Military.com, and other publications. She has produced more than a dozen special series and documentaries including Danger Close, released earlier this year.

Admirers of Quade’s work include former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, who praises her “first-hand portrayals of graphic combat operations,” and Major General (retired) Mike Repass, former Commanding General of U.S. Army Special Forces, who describes Quade as “the real deal.” Repass notes that Quade has spent more time with Special Forces operators than any other reporter. “Alex nails the essence of sacrifice found in America’s Special Forces operators and their families,” he says. “She…is uniquely qualified to tell their intensely-lived, extraordinary stories.”

For her tenacity and extraordinary reporting, Quade has been honored with numerous awards, including two national Edward R Murrow Awards and a Congressional Medal of Honor Society award for excellence in journalism. “My awards belong to the people in my stories, who had the courage to allow me in, to share their stories so we can learn from them,” Quade says.

Now Quade is tackling another challenge: writing a book that offers her behind-the-scenes perspective of secret missions and the “Quiet Professionals” of the Special Forces. Tentatively titled Danger Close (the same as her latest film), the book is slated for publication in 2018. She hopes the book, like her other work, will shed light on the realities of secretive units in combat and its aftermath.

“Witnessing the atrocities of humanity and the suffering of others hurts. The anguish, tragedy, and conflict can be heartbreaking,” she says. “I report the good, the bad, and the ugly. I write and report because I must. The Special Operators never leave anyone behind, and that’s how I feel about their stories. Their stories should all come home too, so that the truth is not left behind.”

The story was written by Nancy Joseph and originally published at the University of Washington’s Perspective.

Alex Quade garners press coverage for film documentaries

MRE Board Member Alex Quade talked about journalism and being an embedded reporter during three press interviews in California, in anticipation of her Special Forces documentaries screening at the Monarch Film Festival this week. [Read more…]

Filmography

- 2016 Danger Close the Alex Quade Story (producer) (filming)

- 2016 Medal of Honor: Special Forces Col. Roger Donlon (Documentary short) (War Reporter) / (producer)

- 2016 Becoming a Green Beret (Documentary short) (War Reporter) / (producer)

- 2015 Behind the Stories of Special Operations (Documentary short) (war reporter)

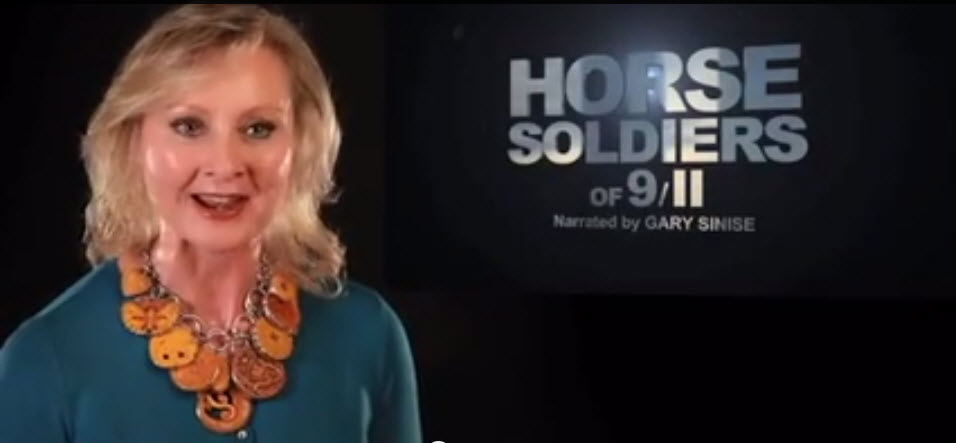

- 2015 Horse Soldiers of 9/11: The Mission Continues – Taliban Capture & Release(Documentary short) (producer)

- 2015 War Memorial (Documentary short) (War Reporter) / (producer)

- 2015 Close Combat Attack (Documentary short) (War Reporter) / (producer)

- 2015 Danger Close: Special Forces Airstrikes (Documentary short) (producer) / (war reporter)

- 2014 Spec Ops Gunship: Danger Close (Documentary short) (producer) / (war reporter)

- Anderson Cooper 360° (TV Series) (War Reporter – 2 episodes, 2005 – 2014) (producer – 2 episodes, 2005 – 2014) (correspondent – 1 episode, 2014)

– Exclusive: SEAL Says He Shot Bin Laden (2014) … (War Reporter) / (correspondent) / (producer)

– Tsunami Stories (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- 2014 9/11 Generation Rangers (Documentary short) (producer)

- 2014 Special Operations Combat Controllers (Documentary short) (producer)

- 2013 Chinook Down (Documentary short) (war reporter)

- 2013 Behind the Stories: War Reporter Alex Quade (Documentary short) (correspondent) / (producer) / (war reporter)

- 2013 Special Forces Combat Outpost Pirelli (Documentary short) (producer)

- 2012 Horse Soldiers of 9/11 (Documentary short) (producer) / (war reporter)

- 2011 Fox and Friends (TV Series) (producer – 1 episode)

– Statue Honors Horse Soldiers (2011) … (producer)

- The Situation Room (TV Series) (War Reporter – 8 episodes, 2005 – 2007) (producer – 8 episodes, 2005 – 2007)

– Combat Search & Rescue Part V (2007) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Combat Search & Rescue Part IV (2007) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Combat Search & Rescue Part III (2007) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Combat Search & Rescue Part II (2007) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Combat Search & Rescue Part I (2007) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Rocket Men of Ramadi (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Hunting IEDs Part II (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Hunting IEDs Part I (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- CNN Newsroom (TV Series) (War Reporter – 2 episodes, 2006) (producer – 2 episodes, 2006)

– Tribute to US Military (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Air Force Thunderbird (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- Lou Dobbs Tonight (TV Series) (War Reporter – 3 episodes, 2006) (producer – 2 episodes, 2006) (executive producer – 1 episode, 2006)

– Military Hero: Marine Goodwin (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Military Hero: Marine Gunnery Sergeant Greer (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Military Hero: Saddam Hussein’s Doctor (2006) … (War Reporter) / (executive producer)

- CNN Sunday Morning (TV Series) (War Reporter – 1 episode, 2006) (producer – 1 episode, 2006)

– Military Couple in Iraq (2006) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- CNN Presents (TV Series documentary) (producer – 4 episodes, 2005 – 2006) (War Reporter – 3 episodes, 2005)

– Wounded Warriors (2006) … (producer)

– Voices from the Tsunami (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Monster: Tracking the Storm (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Children of the Storm (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- House Call with Sanjay Gupta (TV Series) (War Reporter – 1 episode, 2005) (producer – 1 episode, 2005)

– Tsunami Stories (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- NewsNight with Aaron Brown (TV Series) (War Reporter – 2 episodes, 2004 – 2005) (producer – 2 episodes, 2004 – 2005)

– State of Emergency (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Giving Troops a Second Chance (2004) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

- Paula Zahn Now (TV Series) (War Reporter – 4 episodes, 2005) (producer – 4 episodes, 2005)

– President Bush Recognizes the Brothers in Arms (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Brothers in Arms (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Married Medics in Iraq (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

– Wounded Warriors Stories (2005) … (War Reporter) / (producer)

Alex Quade provides advice on being a war reporter

In this video, Alex Quade gives tips and serious advice for journalists who want to cover wars from the front lines. [Read more…]

About Alex

Alex Quade

War Reporter Alex Quade covers U.S. Special Operations Forces on combat missions. She is the only reporter, male or female, ever embedded long-term with these elite, secretive units downrange. She is the recipient of two national RTDNA Edward R. Murrow Awards, as well as the Congressional Medal Of Honor Society’s “Tex McCrary Award For Excellence In Journalism” for her war reportage.

The Medal of Honor recipients present the award to individuals who, through their life’s work, have distinguished themselves by service or unbiased coverage of the United States Military through journalism. Prior recipients of this prestigious award include legendary broadcasters Tom Brokaw, Mike Wallace, Tim Russert, Paul Harvey, and author Joe Galloway. The Congressional Medal of Honor Society recognized Ms.Quade, “for her courageous reporting and honest news coverage.”

Ms.Quade started her career as a White House Press Office intern during the Persian Gulf War, for President George H.W. Bush. She has worked in television for Fox News and CNN, both domestically and internationally. Extreme storytelling and silent risk-taking lie at the heart of what she does. As a “one-man-band”, she embeds with elite combat units several months at a time, producing exclusive, long-form, special series and documentaries.

“Chinook Down” is her investigation into the Taliban surface-to-air missile shoot down of a U.S. Chinook helicopter in Afghanistan, that killed all on board. Alex Quade was supposed to be on that helicopter. She survived to report firsthand on the recovery efforts, which included a fierce firefight. The mission involved Army Special Forces Green Berets, Air Force Special Operations assets, Parachute Infantry Regiment and Combat Aviation Brigade elements. Ms. Quade gathered material about the attack on the helicopter, obtained previously unreleased documents from the Pentagon and collected video from soldiers and pilots on the scene. The result of her work is a video special for The New York Times – At War website. “Chinook Down” garnered a billboard in New York’s Times Square, and is now in film festivals nationwide.

Ms.Quade produced and directed a documentary about Special Operations Forces in Afghanistan, “Horse Soldiers of 9/11,” that is currently showing in film festivals nationwide. Narrated by actor, Gary Sinise, Quade’s film expands her original investigative reports for The Washington Times, CNN.com, and The Daily Caller. Vice President Joe Biden quoted Ms. Quade’s stories during the dedication of a monument paying tribute to the secretive warriors, near ground zero in New York. (FOX affiliates, Armed Forces Network, and the Pentagon Channel re-broadcast the event and Quade’s stories worldwide.)

In Quade’s documentary short “9/11 Generation Rangers”, she followed special operations Tier-1 Army Rangers for 5-years, beginning with their meeting President Barack Obama at the 65th Anniversary of D-Day in Normandy, France. Ms.Quade brought attention to Sgt.1st Class Cory Remsburg, who was critically wounded in Afghanistan shortly thereafter. President Obama recognized Remsburg during his State of The Union address; and again at the 70th Anniversary of D-Day in Normandy. There, the President praised Ranger Remsburg and this “9/11 Generation” of warriors, comparing their call to serve, to that of the “Greatest Generation” from World War Two.

“Combat Outpost Pirelli” is Quade’s intimate look at a Special Forces A-Team in combat, during which one Green Beret was killed in action. Ms.Quade followed the A-Team and their families over a 5-year period, through various deployments. Her video and long-form print and web articles were critically acclaimed throughout the Special Operations community.

In Quade’s award-winning documentary, “Wounded Warriors” for CNN Presents, she was the first reporter to obtain unprecedented access to injured troops, premiering an exposé on the ravages of battle and the care given at every echelon in war zones. Senator Bob Dole personally asked Quade to provide copies of her video to him, to share with Health and Human Services Director Donna Shalala and President George W. Bush’s Commission On Care For America’s Returning Wounded Warriors; to help educate decision-makers and troop caregivers. Today, military units include her piece in their pre-mission training.

Quade’s commitment to providing viewers “ground truth” behind the conflict and disaster zones around the world has kept her “boots on the ground”. For her award-winning “Brothers In Arms” for CNN’s “Paula Zahn Now”, Quade followed an Army National Guard family for 18-months, from Idaho to Iraq, and back. Following the program’s airing on CNN, President George W. Bush publicly recognized the family for their bravery.

Quade’s dedication to sharing military stories from all angles and giving voice to those in the fight is evident in “Hunting IEDs” for CNN’s “The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer” and CNN’s “Anderson Cooper 360”, her series that gave viewers their first inside look at a dangerous Marine Platoon mission in Fallujah. The U.S. Department of Defense Joint IED Defeat Task Force has used her piece as a case study.

Quade expanded her behind-the-scenes access in “Combat Search And Rescue” for CNN’s “The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer” and “The Glenn Beck Show” on Headline News (HLN). Her in-depth special incorporated never before told, high-risk rescue missions from the frontlines of Iraq and Afghanistan with U.S. Special Operations Forces.

Quade has embedded with every branch of the U.S. military and spearheaded CNN’s Air Force coverage from a secret air base during the “Shock & Awe” campaign. Her “Military Hero” segments aired on CNN’s “Lou Dobbs Tonight,” and CNN’s “This Week At War.”

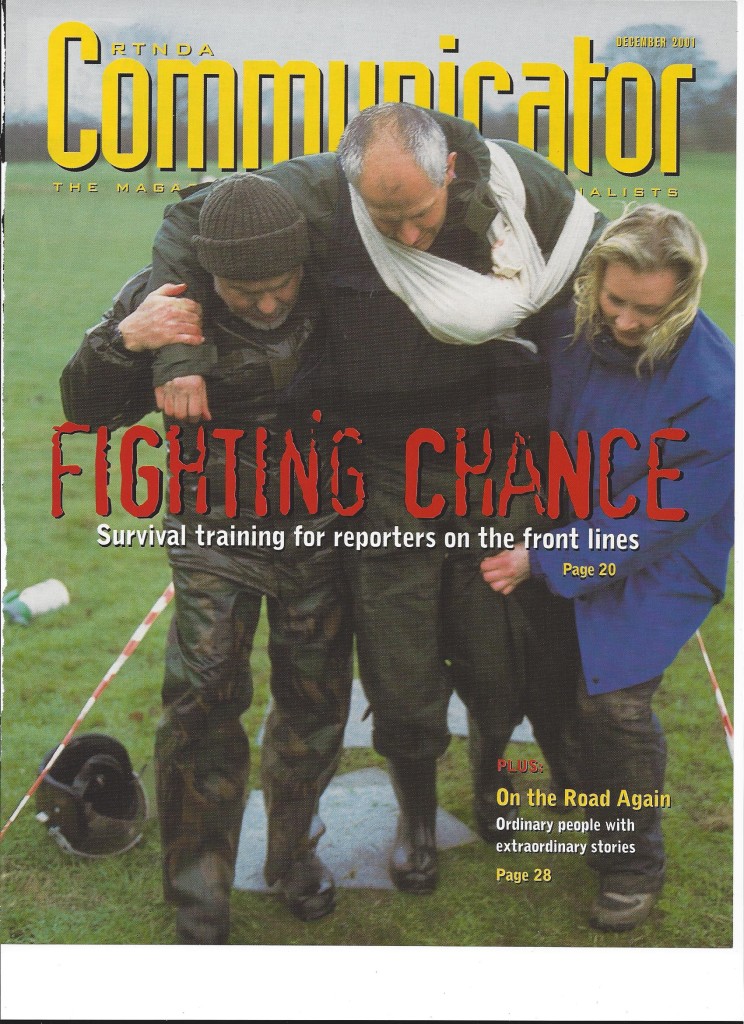

Other awards for Quade’s war reportage include: A Military Reporters & Editors Award, two American Legion “4th Estate Awards”, an Armed Services YMCA “Angel Of The Battlefield Award”, a U.S. Army National Guard Bureau “Minute Man Award”, an International Health & Medical Media “Freddie Award”, two CINE “Golden Eagle Awards”, an American Women In Radio & Television Association “Gracie Award”, a Newswomen Of New York “Front Page Award”, two Society of Professional Journalists “Green Eyeshade Awards”, a “Communicator Award” and a “Telly Award.” Her in-depth, frontline reporting on the Asian Tsunami was listed as part ofCNN’s “DuPont Columbia Award” win; her special pieces for “CNN Presents” were part of CNN’s “International Documentary Award” win; and her Hurricane Katrina and Rita stories, while embedded with military emergency response teams, were part of CNN’s “Peabody Award” win. Ms.Quade has also been nominated for several National Association of Television Arts and Sciences regional “Emmy Awards”, as well as honored by the New York Festivals and regional Associated Press Broadcasters Association. Her magazine articles were part of an “Excel Award” for General Excellence (Magazine Group Award).

Quade’s articles have appeared in news magazines such as “Dangerous Assignments”, “Communicator”, “National Press Photographer”, “The Drop – Special Forces Association Magazine”, “Soldier of Fortune”,“Veterans March” magazine, “USO On Patrol” magazine, “Columns” magazine, and“The American Headache Society” (regarding military Post Traumatic Stress and Traumatic Brain Injuries). She has also written for CNN.com, The New York Times “At War” blog, Military.com, The Washington Times, the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), and Radio, Television, Digital News Association (RTDNA).

Quade has appeared live on CNN many times, and is also known for “finding the humanity in inhumane conditions”, not only in combat zones, but also in other hostile environments and natural disasters. Despite ongoing civil strife and the Aceh Separatist Rebel Movement, Quade was one of the first reporters to get into Bande Aceh, Indonesia, ground zero for the devastating Asian tsunami. She was one of few reporters to return a year later. Following her compelling stories on orphans of the storm for “CNN Presents”, and her special series for CNN’s “Anderson Cooper 360”, there was an outpouring of aid organization and viewer offers, including U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein (D – California), to help the children specifically in Quade’s pieces. The reaction to Quade’s distinctive stories from Hurricane’s Katrina and Rita for “CNN Presents,” was similar. (In fact, Cher, the Academy Award-winning singer and actress, contacted Quade to help the people in her hurricane stories.)

Ms. Quade moderated the Defense Forum on Capitol Hill, and the Warrior Family Symposium, both aired live on C-SPAN. For several years, she’s helped plan and moderate the annual Washington State Women Veterans Conference. Quade also moderated the groundbreaking “Patriots At Home” conference with Medal of Honor recipient Drew Dix. Every chamber of commerce in the United States near a military installation now owns a DVD of this results-oriented event to help their leaders reintegrate returning war veterans back into their civilian communities.

In addition to serving as a White House Intern, Quade was a student delegate at NATO’s “Conference on The Atlantic Community”, and is a graduate of Georgetown University’s “Institute of Political and Ethical Journalism”. She holds three separate degrees from the University of Washington: Political Science, Communications and Speech. Quade was an East-West Center Fellow in China, is an alumna of the selective University of North Texas Mayborn Literary Non-Fiction Writers Conference, the Medill National Security Journalism Initiative (Covering the Military Home and Abroad Conference), and is a graduate of The Poynter Institute’s “Power Reporting.” She attended the University of Kansas School of Journalism/U.S. Army Combined Arms Center “Military and Media Program” at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, and The Goethe Institute in Frankfurt, Germany.

Alex Quade serves on the Advisory Board of Medal of Honor recipient Drew Dix’s “Center For American Values.” She helps our nation’s other Medal of Honor recipients by raising public awareness of their role model examples of heroism, through her stories, and their “Character Development Program,” which aims to inspire school children to do the right thing when nobody’s looking.

Ms. Quade serves on the Board of Military Reporters & Editors Association, the association of military journalists. The association exists to advance public understanding of the military, national security and homeland defense; to educate and share information with its members and the public on best practices, tools and techniques for such coverage; to represent the interests of working journalists to the government and military; and to assure that journalists have access to places where the U.S. military and its allies operate. Quade is a member of Investigative Reporters and Editors, Inc., the Society of Professional Journalists, and Radio Television Digital News Association.

(New York – April 27, 2016) — Mauro DiPreta, Publisher of Hachette Books, announced today the acquisition of DANGER CLOSE, a nonfiction narrative by award-winning war reporter, Alex Quade, who covers Special Operations Forces on combat missions downrange and who has experienced unprecedented access to these elite combat troops.

(New York – April 27, 2016) — Mauro DiPreta, Publisher of Hachette Books, announced today the acquisition of DANGER CLOSE, a nonfiction narrative by award-winning war reporter, Alex Quade, who covers Special Operations Forces on combat missions downrange and who has experienced unprecedented access to these elite combat troops.