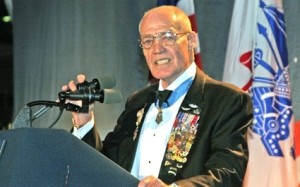

Medal of Honor recipient made impression

Col. Robert L. Howard

As young journalists bootstrapping our way up the news ranks, our mentors are usually editors or executive producers. If you’re a journalist, what you’re about to read may come as a bit of a shock. My mentor was not in the news business. Far from it, though he made some news in his day.

I’ve come to learn, it’s a good thing in our profession, to try to understand people — or groups of people — who despise you. And on the flip side, this may come as a shock to anyone reading this who happens to serve in the secretive world of Special Operations; a community with no great love for reporters, especially after the “Tailwind” story on CNN in the 1990s which eventually was rescinded. But I hope they will read the following; even though it’s from a purported “tree-hugging, Birkenstock-wearing, liberal-media-puke.”

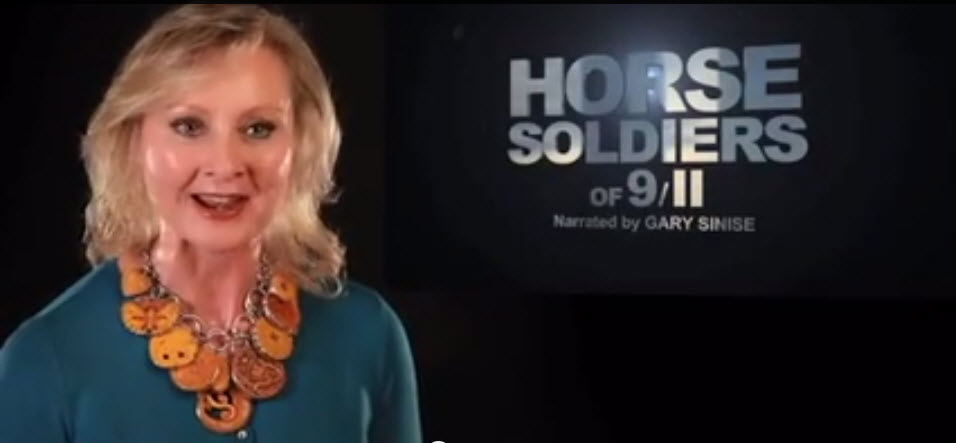

As a lone, woman war reporter covering U.S. Special Operations forces on combat missions downrange, an unexpected mentor came into my life. This unlikeliest of sources hated reporters. Despite that, he “chose” me, treated me as an adopted SON, and taught me everything I need to know that matters.

Love him or hate him, everyone respected Medal of Honor recipient Col. Robert L. Howard (or “Mean ol’ Ranger Bob” as I liked to call him) for his bravery during five tours in Vietnam, mainly with the Studies and Observations Group. He was one of the most decorated soldiers in U.S. history; nominated for the Medal of Honor three times.

Bob said many people in that community deserve medals for all the unheralded things they’ve done, which, due to their classified nature, lack of witnesses, nor write-ups, few Americans will ever know about. He said he wore his Medal of Honor for each of them.

When I was with him, and his family, during his last weeks in hospital in Texas in 2009, he asked me to share a last “tasker” for each man or woman serving in Special Operations: “Continue the Mission.”

And he tasked me, too: “You must be tough as woodpecker lips,” Bob told me. “You must do the thing you cannot do. Whatever your fate may be… you make it happen along the way.”

He emailed advice almost every day, especially when I was downrange, as an embedded war reporter, covering “his” Green Berets on combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was excited I was to spend time with “his” Rangers, too. He encouraged me to make a difference through the war stories I do and said he admired my perseverance.

Col. Bob Howard and Alex Quade.

“Alex, truth in reporting is a virtue; without unnecessary exploitation of facts. It’s about trust and honest sincerity. Military dependents resent the absence of their loved one and will turn to you for the rest of the story,” Bob replied. Which is why he hassled me every day I was back stateside.

“Lady, are you up exercising your talents?” He’d email early in the morning. If I didn’t hit “send” to reply quick enough, it was, “Get your butt out and ruck-march!” You see, Bob expected me to follow his strict regimen: Adding weight in a rucksack while picking up speed and increasing distance. As a septuagenarian, he still got up at 4:30 every morning to do physical training. He could still walk 25 miles and carry a ruck, and he was not shy about saying, he had “No patience for fat people, women, or hurt feelings.”

“You must carry your own load at squad or fire team level,” he said. “But I’m scaring the socialites and their little dogs in Central Park,” I countered. Bob didn’t care. His orders were clear: “Don’t hold back the men downrange!”

He said he felt like he was “sending me off to face evil” every time I deployed. He told me to carry a copy of the Koran, adding, “Learn some basic Farsi and practice it on the locals.” And, since I have no patience, he admonished: “Never be quick to take the next step without knowing where it leads you.”

“Seek out the good sergeants; you’ll know who they are. They’ll set you straight,” Bob advised. “Keep your eyes up and your butt down,” he said. “Stay in the shadows. Blonde hair makes a good target. If I can see you, I can kill you!”

He reiterated that fact one night in Landstuhl, Germany, before I headed back to Iraq and Afghanistan. One moment he was casually smoking a cigar, the next, he literally had my life in his hands. I’ll call it the “two-fingered, Vulcan death-grip” on the back of my neck, which brought me to my knees in an instant and made Medal of Honor recipients Staff Sergeant Drew Dix (5th Special Forces Group) and Command Sergeant Major Gary Littrell (Ranger Battalion) smile.

“That’s what you need to know how to do,” he said, during his impromptu combative lesson. But what I got out of that lesson was: Damn! He may look old, but never underestimate Bob Howard!

Bob must have known for a long time that he was fighting his last battle with the Grim Reaper. And like all soldiers, did not want to die alone. “This’ll keep ya motivated!” He said, shoving a Ziploc baggie at my chest. Inside was a bloody, nasty-looking piece of shrapnel freshly removed from near his frontal lobe just two weeks before. Just what every girl wants, right?

“It’s a real piece of North Vietnamese Army shrapnel fired from a 75-mm recoil-less rifle, that hit to the left front of me while I was firing at the enemy position, from a prone position, about 300 meters away,” Bob explained. “They rushed to clamp the arteries and veins to keep me from bleeding to death and left the shrapnel in. Had a headache for 42 years. First few days after removal recently, messed up my equilibrium.”

But the former member of Delta, the Green Berets and Ranger Battalion, who’d braved all the world’s hostile environments, was starting to feel the cold. So I gave him my “Woobie,” the blanket I’d carried in Iraq and Afghanistan. Sitting in his hospital room, in the wee hours, he told me, I was the one who looked cold; so he made me wear his beanie, that old, black, Ranger patrol-cap had never been washed in 25 years. He said, just looking at it on my head, made him feel warm.

Looking for things to appreciate in tough situations is what helped Bob through. “Look for Orion’s Belt. It is one of the most beautiful sights. I’ve lain in place, concealed, looking up at it many times while in Vietnam through sporadic jungle canopy,” he quietly mused.

“This is no bullshit!” Bob turned serious. “I challenge you to stay alert, stay safe, watch your back, and return home to share your stories and experiences with the public that need to be reminded,” he pointed his finger at me.

He asked me to tell all “his men”: Always “Lead from the front,” because that’s what he did. And: “Charlie Mike,” or, “Continue the Mission”. The last thing Bob said to me was, I “can kiss him in his coffin.”

Despite my belief that Mean ol’ Ranger Bob would take out the Grim Reaper with the pistol strapped to his calf, cancer took what the enemy never could. Col. Robert L. Howard passed away the day before Christmas Eve, 2009. Every morning since then, I look at my email… half expecting a butt-kicking message from him from the grave. His lessons still sound off like a cadence to my footfalls when I go running: “Charlie Mike… Continue the Mission… Charlie Mike…”

No, my fellow journalists… I did not drink the Kool-Aid.

Alex Quade visits grave site of Medal of Honor recipient, Col. Bob Howard at Arlington National Cemetery.

Now, whenever meetings bring me to the “five-sided wind tunnel” on the Potomac (the Pentagon) I go visit Bob. The birds at Arlington National Cemetery seem to target his headstone. Bet that pisses him off, I think, touching his shrapnel hanging on a chain around my neck. But then I know, just like Clint Eastwood, he would have squinted-up his eyes, like he always did, laughed and grinned widely.